As part of the FoodBioSystems Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP), I participated in a collaborative group project known as the Tiger Team. Alongside four other researchers, we worked with Natural England on a project titled Climate Change Adaptation Planning on Sites of Special Scientific Interest. This experience deepen my understanding of the urgent and complex realities of climate change. No longer a distant concern, climate change is a present and growing force. Around the world, communities are shifting from focusing solely on mitigation to developing meaningful strategies for adaptation.

This led me to a new question: if we can talk about adapting to climate change, why not also explore how humans have adapted to another persistent challenge, parasitic diseases?

Parasitic diseases are far from eradicated. In fact, climate change is contributing to the resurgence of some that were once under control. So how have humans historically responded to the constant threat of parasites? And how can we continue to adapt in a world shaped by changing climates and shifting disease patterns?

In this blog, I explore how humans, through biology, culture, behavior, and policy, have not only survived but coexisted with parasites and transformed that coexistens into a survival strategy.

Parasites as Evolutionary Pressure

Parasites have long influenced how humans and other animals live, behave, and evolve. They are not just biological threats but also powerful forces of natural selection. Much like predators, parasites can shape where species live, how they behave, how they reproduce, and how they interact with their environment.

Over thousands of years, repeated exposure to parasites has driven the development of avoidance strategies in many animals, including humans. These strategies, such as avoiding contaminated water or altering feeding behaviour, may have started as individual responses. But when the threat of infection persists across generations, such behaviours can become ingrained in a species’ biology, appearing as fixed traits or physiological changes (Hart, 2011).

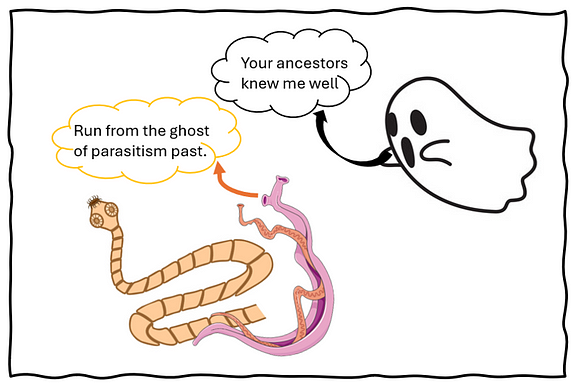

This idea is sometimes referred to as the “ghost of parasitism past.” It suggests that some species today show few signs of parasitic infection not because they are immune, but because they have evolved so effectively to avoid parasites. These adaptations, such as selecting cleaner habitats or developing thick skin or fur, have become built into their biology (Chaumont et al., 2021).

In humans, we see similar evolutionary legacies. One well-known example is the sickle cell trait, which, while harmful in some contexts, offers protection against malaria. This is a classic case of a genetic adaptation shaped by parasitic pressure. Even the complexity of the human immune system reflects a long history of exposure to a wide range of parasites.

Interestingly, some birds and primate species host fewer parasites than expected based on their environment or social behaviour. This raises the possibility that they have evolved invisible defences, either behavioural or physiological, that make them less hospitable to parasites. Though often subtle, these legacies reveal a deeper story of survival and adaptation shaped by ongoing biological struggles.

Parasites have not just challenged us. They have helped shape who we are. Our evolutionary history is, in many ways, written by the diseases we have had to endure.

Socio-Cultural Adaptations to Parasitic Diseases

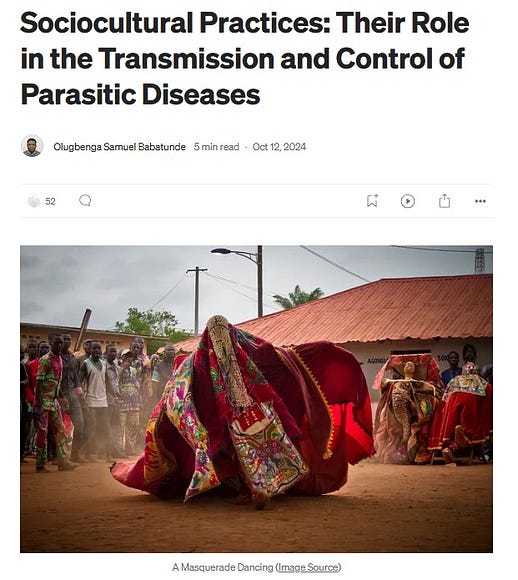

In my previous blog, Sociocultural Practices: Their Role in the Transmission and Control of Parasitic Diseases, I explored how everyday behaviours can influence the spread of parasitic infections. Interestingly, many of these practices are not merely coincidental. They have emerged as adaptive responses to life in parasite-endemic environments. Shaped over generations by lived experiences rather than formal science, these cultural adaptations offer valuable insights into how communities manage parasitic disease risks through tradition and behaviour.

Across many cultures, hygiene routines and food practices have evolved into effective, if often unconscious, defences against parasitic infections. Handwashing before meals or after contact with soil, common in regions like Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, helps reduce exposure to soil-transmitted helminths. In areas such as Tanzania’s Southern Highlands, communities began boiling pork thoroughly after observing worms in meat, a practice later reinforced by health officials. Similarly, traditional spices like garlic and turmeric are valued not only for their flavour but also for their antimicrobial properties (Møller et al., 2022).

Cultural norms around communal eating have also adapted to reduce health risks. Some communities now incorporate handwashing rituals, individual servings, or disposable utensils during festivals to prevent faecal-oral transmission, highlighting how illness experiences shape grassroots public health responses.

In agrarian societies, evolving agricultural and animal-handling practices also reflect adaptations to parasitic threats. While older methods, like using untreated wastewater or free-roaming livestock, contributed to parasite transmission, many communities have since shifted to safer approaches. These include fencing animals, rotating grazing areas, using treated water, and deworming livestock. Even without formal veterinary support, local knowledge and peer advice have helped shape practical responses. Practices like avoiding sleeping near animals or designating specific areas for them are further examples of culturally rooted disease prevention.

Together, these shifts underscore how socio-cultural practices can serve as informal yet powerful tools in managing parasitic disease risks, providing a foundation for community health that is deeply embedded in tradition.

From Coping to Strategy: Modern Human Adaptations to Parasitic Disease

In recent decades, human responses to parasitic diseases have evolved from survival-based reactions to deliberate, science-informed strategies. These adaptations represent a shift in how societies understand and manage parasitic threats, combining innovation, local knowledge, and environmental awareness to reduce risk and build long-term resilience.

- Medical Innovation and Access to Treatment

Advancements in biomedical research have equipped humanity with targeted tools to fight parasitic infections. Vaccines like RTS,S for malaria, along with antiparasitic drugs such as praziquantel, albendazole, and ivermectin, have become cornerstones of large-scale disease control programs. These treatments, widely used in mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns, represent a deliberate, health-system-level adaptation to reduce the burden of parasites. However, the growing challenge of drug resistance signals the ongoing need for adaptation through continued scientific innovation.

2. Climate-Aware Health Planning

As parasitic disease patterns shift due to climate change, public health systems are adapting through predictive modelling and climate-resilient infrastructure. Risk mapping, early warning systems, and improved drainage or vector control strategies reflect a proactive stance: planning for future outbreaks based on environmental trends. This marks a key adaptation, transforming knowledge of climate-parasite dynamics into preventive public health action.

3. Revitalizing Indigenous Knowledge

Another modern adaptation involves reclaiming and integrating indigenous knowledge into mainstream health strategies. Traditional practices, such as the use of herbal antiparasitic, natural insect repellents, and avoidance of high-risk landscapes, are increasingly recognized as effective, culturally embedded defences. Collaborating with local communities not only strengthens program design but also ensures these adaptations are accepted, sustained, and tailored to the lived realities of those most at risk.

Bridging to the Future: Evolving Human Responses to Parasitic Threats

As the boundaries between ecosystems, animals, and human populations continue to blur, parasitic diseases are no longer confined by geography or predictability. Climate change, urbanization, migration, and global trade have collectively reshaped the parasitic threat landscape, demanding not just better science, but smarter systems. Bridging to the future means transcending siloed responses and building interconnected strategies that are resilient, inclusive, and anticipatory.

1. One Health: An Integrated Defence Network

The One Health paradigm emphasizes that human, animal, and environmental health are inseparable. Parasites thrive in the gaps between sectors, spreading through contaminated water, shared food chains, and multispecies hosts. Addressing this requires more than medical intervention; it calls for collaboration between physicians, veterinarians, ecologists, anthropologists, and policymakers. Through coordinated efforts like zoonotic disease surveillance, sustainable agriculture, habitat protection, and cross-sector education, One Health moves beyond symptom treatment to systemic prevention.

2. Building Resilient Systems, Not Temporary Solutions

True adaptation isn’t reactive, it is structural and sustained. This means investing in surveillance systems that detect emerging threats early, health infrastructure that reaches remote populations, and education that empowers local communities to recognize and respond to risk. Long-term funding, inclusive policy design, and respect for indigenous and local knowledge are not optional, they’re foundational. By embedding parasitic disease prevention into broader development goals, such as clean water access, climate adaptation, and food security, communities can shift from crisis response to durable health sovereignty.

Conclusion: Resilience in the Face of the Invisible

Parasites have long been an invisible thread running through human history, shaping our biology, behaviors, and beliefs. But what’s remarkable is not just our ability to endure, but our capacity to adapt and thrive. From ancestral rituals to modern vaccines, from community wisdom to cross-sector collaboration, we have never stood still in the face of parasitic threats.

As climate change reshapes the global disease landscape, our challenge now is not only scientific, it’s social, cultural, and environmental. The future will demand more than individual action; it will require shared responsibility, inclusive policies, and a deeper respect for the knowledge that communities have built over generations.

In the story of human resilience, parasites are not just foes, they are catalysts for progress. And through adaptation, innovation, and unity, we continue to write a new chapter, one of informed action, global health, and hope.

The journey towards becoming my name is going to take a lifetime and, in the end, I hope to say I am Olugbenga Samuel Babatunde.

The journey towards becoming my name is going to take a lifetime and, in the end, I hope to say I am Olugbenga Samuel Babatunde. Early life as a child had a serious impact on my immeasurable concern for the welfare and health of humans. Growing up in my home town Ifon, Ondo State, Nigeria. I observed face to face the effect of infectious diseases on the people living in the town and even my relatives were not left out. The countless loss of lives mostly that of children resulting from diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, cholera to mention a few. To make the case worst many people in the rural community are not aware of infectious diseases and they give it different sorts of names. Most people infected are stigmatized. For instance, lymphatic filariasis in some part of Benue State, Nigeria is attributed to adultery or witchcraft but they are not aware that the pathogens are transmitted by mosquitoes.

Early life as a child had a serious impact on my immeasurable concern for the welfare and health of humans. Growing up in my home town Ifon, Ondo State, Nigeria. I observed face to face the effect of infectious diseases on the people living in the town and even my relatives were not left out. The countless loss of lives mostly that of children resulting from diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, cholera to mention a few. To make the case worst many people in the rural community are not aware of infectious diseases and they give it different sorts of names. Most people infected are stigmatized. For instance, lymphatic filariasis in some part of Benue State, Nigeria is attributed to adultery or witchcraft but they are not aware that the pathogens are transmitted by mosquitoes. Infectious diseases do not only affect the health sector but also resulted in lower investment and a substantial loss in; private sector growth, agricultural production, cross-border trade (restrictions on movement, goods, and services increased) as we can see in the present pandemic of Covid 19. This ignited a fire within me to become the change agent needed by the community in addressing health issues.

Infectious diseases do not only affect the health sector but also resulted in lower investment and a substantial loss in; private sector growth, agricultural production, cross-border trade (restrictions on movement, goods, and services increased) as we can see in the present pandemic of Covid 19. This ignited a fire within me to become the change agent needed by the community in addressing health issues. Therefore, I need to write to create awareness about the impact of infectious disease on people’s lives. I need to write to inform them about the mode of transmission, prevention, and treatment of most infectious diseases. I need to write to inform them of the importance of personal hygiene, the use of mosquito nets, the need for a balanced diet, the need for routine laboratory checkups, etc. I just need to write.

Therefore, I need to write to create awareness about the impact of infectious disease on people’s lives. I need to write to inform them about the mode of transmission, prevention, and treatment of most infectious diseases. I need to write to inform them of the importance of personal hygiene, the use of mosquito nets, the need for a balanced diet, the need for routine laboratory checkups, etc. I just need to write.